From the editor: Cami Quinteros, a staff architect and project manager, recently took a trip to Spain for an intense two week course on traditional architecture. Here is their summary of the knowledge brought home from the course:

Hidden away in northern Spain, between Asturias, Castille and the Basque Country, is the region of Cantabria. Known for its rich landscape, the cave of Altamira, and rock-carved medieval churches, Cantabria is a summer attraction for many.

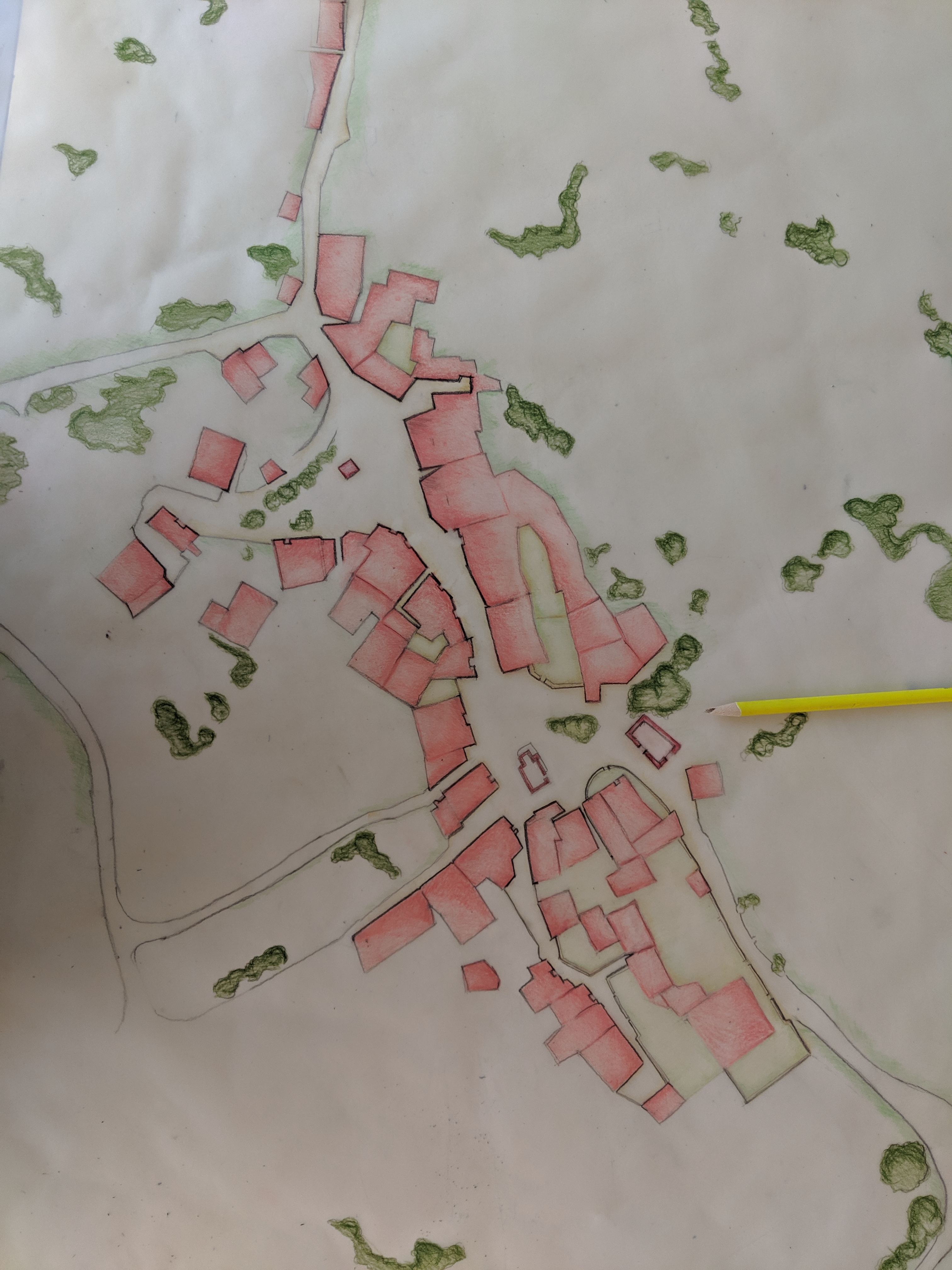

The Cantabria Summer School of Traditional Architecture is a two-week program in which architects from around the world gather to draw, analyze, and learn from the traditional methods and styles present in the region. Our base was in Polientes, the capital of the valley of Valderredible. Valderredible's architecture is a hybrid of "Casa Montañesa" from the mountains of Cantabria and that from northern Castille.

The houses, made out of sandstone, have small windows that keep the interiors warm in the winter. Beautiful south-facing balconies dry foods and gain passive solar heat in the summer. The houses, organized in a tight urban fabric, become relaxed at the edges; giving way to a seamless transition between urban and rural.

Moreover, the Valley of Valderredible houses 53 small towns with deep roots to its land and an identity inextricably linked to cow herding, the planting potatoes and cereals, and access to water. Every town invites you to walk. You will want to get lost in the landmarks, water fountains, churches, tower houses, and inspiring mews.

We were invited to Valderredible to provide an outsider's perspective to a problem in rural Spain. The rural world is facing depopulation due to migration to cities. We arrived during a brutal heat wave striking most of western Europe. It then became clear that the Valley of Valderredible would eventually become a key player in hosting climate refugees from southern and central Spain. Due to its geography, Valderredible keeps a dry and pleasant climate even in the middle of the summer.

So, how does one use traditional architecture methods to face the possible growth of a town due to climate change? How does one hold the town's identity? How does one learn from locals, and plan new buildings according to that knowledge?

The first week of the course was dedicated to understanding Valderredible, its geography, and its architecture. We visited a couple of towns per day, creating analytical drawings that we later discussed as a group. In the afternoons and evenings, master classes were given by local experts regarding regionalism, archeology, history, and building methods. We even had a master carpenter, and general contractor come and talk to us about how to build with traditional methods.

As the first week ended, the group began to understand key elements of the region:

- The materials used for construction were all local. These materials also could go back to the earth once the building was no longer pertinent. This method is called "Leave No Trace Architecture," which integrates with the cycle of nature. All exterior walls were sandstone, and all openings used wooden windows and doors, all mortar was earth-based, all finishes were lime-based.

- The balconies on the south-facing sides of the buildings, once used for drying foods, are now used as "soleras." A solera is an area that soaks the heat of the sun. This re-purposing was one of the many examples in which we saw locals understand the climate of their region and take advantage of it with simple design methods.

- Building maintenance was a source of pride. We spoke about how in other regions of Spain people would gather yearly to re-finish facades with limewash and leave the town sparkling. In Valderredible, one could see that even though families had migrated to urban areas, they spend time and money in their hometown to have it look beautiful and well-maintained.

The second week focused on our proposal for Polientes – how could a town of 100 people prepare for hosting possibly a couple thousand by 2050? And how did the people of Polientes feel about it?

Amazingly, as we became friends with a few locals, the constant feedback we got was "don't change my town" – the people of Polientes loved their town and didn't want to see it become yet another metropolis. So, with our new regional knowledge, we set out to do what they asked for – to conceive a plan where the town of Polientes could grow without changing, where the relationship to nature remained intact, where people remain undisplaced by gentrification, and where the locals could thrive as newcomers eventually arrived.

We divided the town into 8 sections and set out to work on specific projects: while some groups focused on the improvement of already existing areas, such as the town entrance or expanding the school complex, other groups focused on new areas of development, as well as connecting some modern constructions in the periphery of town to the main urban fabric. We created areas of mixed-use, without a concept of zoning, but instead, of community and human-scaled spaces. We used beauty and curiosity as our tools to guide people: if we wanted someone to take a turn, we would make a beautifully curved mew that invited the curious to see what beauty held beyond. We took away focus from cars and made mostly pedestrian streets. We also took the local typology and applied it to modern needs, such as apartment buildings, community gardens, and digital libraries.

However, what inspired us to leap into applying local tradition to modern needs, was the mix of professionals that came to visit us in that second week. We had architects working on contemporary buildings using the means and methods of traditional architecture and at times mixing them with high-performance technologies. Such innovation within the tradition of typologies was fascinating.

We spoke about the concept of "invariables" – elements that very slowly change over time but still act as a link between the present and the past. We also spoke about the importance of site analysis for the proposal of new buildings or building refurbishments. All and all, the second week, was about applying the methods learned from the past into today's world.

As we quickly approach our reckoning of climate change, and the effects it will have in our lives, rescuing traditional methods and occupying existing buildings will become more and more common. Moreover, I hope that in both modern and traditional architecture we can adopt an ethos of sustainability that goes beyond energy usage but in which we can become one with the cycle of nature, as "Leave No Trace Architecture" does. For me, the Cantabria Summer School of Traditional Architecture was a reminder and a refreshment: There are so many options for us to do right by the world as we leave our mark in the built environment.

Interested in Continuing Education?

Eco Supply offers several AIA CES courses featuring our sustainable building products. You can request a course for your firm by clicking the button below.